The Pang

February 22, 2011

February 22, 2011  Post a Comment

Post a Comment “I still get that little pang when I see you.” That’s what my husband says to me every now and then when he walks in the door and sees me. And even if I’m mad at him -- even if I’m standing there with my hands on my hips, head cocked to one side--- it still makes me smile. It stops me right in my tracks because there really isn’t anything else he could say that would make me feel so completely …. loved.

The “pang” is the equivalent of a schizzle. You know that feeling. At least I hope you do. It’s the sensation of things flipping over a little bit inside you, somewhere down below your belly button. It’s what happens when you think about him or her, when you contemplate and anticipate the night to come or replay the one you just had. At my age, maybe the pangs aren’t quite so dramatic. They’re more like pulse points. They simply let you know that the heart is still alive and kicking.

The fact that my husband and I have been married for 23 years and he is still “panging” should be reason enough to keep him around. Whatever he’s done, like leaving his dry cleaning stubs on my dresser (two feet from the wastebasket) or making me repeat something for the third time because he is only partially listening ( my voice is white noise), these things seem vastly less important when he pangs.

Marriage is a tough gig. Take two people who are desperately in love and full of lust and then shackle them together through the years. The “I can’t wait to get him in bed” feeling begins to evolve into “if that bastard snores again I’m going to stuff the pillow down his throat.” The candlelit meals and champagne toasts with entwined arms ultimately give way to the routine of unloading the dishwasher. It’s inevitable. Marriage is about the business of living; of living together and making it work. There is nothing romantic about a clump of hair in a shared bathroom shower drain or feeding a family of six night after night. But this routine becomes a kind of necessary glue that helps it all hang together. For most of us anyway.

My husband is easy on the eyes. People are always telling me how handsome he is. And as smitten as I was by all facets of him when we first started dating, I chose to give my heart to someone who would always challenge me intellectually, who got my sense of humor and who could, in turn, make me laugh. I married a kind man, which was vital to me. But most importantly, I married someone with whom I imagined I would never, ever, have to sit across from 45 years later at a Denny’s buffet, chewing slowly and with absolutely nothing left to say. And after all, handsome is as handsome does. You stop seeing the outside after a while, so you’d better love what’s inside.

So how do folks keep a marriage going? What are the secrets, the keys, the things people do? I get asked this a lot, especially from younger people who seem to think that Bob and I have it all figured out. But I’m loath to be a poster child for matrimony. I know this: there is no perfect marriage. You need mutual respect, the ability to compromise and negotiate, love in all kinds of doses, a few shared dreams, a long leash and a big sense of humor. Laughter is key. Laugh together, laugh often, laugh when you want to cry, and laugh at yourself. When you are in it for the long-haul, self-deprecation and a dose of humility become as sexy as George Clooney. And when the chips are down or you hit a rough patch, gallows humor can ease you through many of the tough times. It’s much harder for the heart to break when you’re laughing out loud.

I think in the end, as my husband says, you can simply get lucky. You can’t possibly predict how someone is going to grow or evolve (or not) in the years to come. You don’t necessarily think about the genetic time-bombs of cancer, Alzheimer’s or depression that can lurk in the ancestral closet of your combined gene pools or the way your lover was parented (or not) as a child. These are things that will occur to you later. Sometimes, they’ll be enough to stop you in your tracks.

It’s fairly easy to trace the ways that love can erode. Being a responsible adult is sobering. There are taxes and credit card bills and mortgages, and then you add kids and dishes and laundry and you find yourself talking out loud about “pee” and “poopy” and germs and telling everyone to “wash your hands” or “it’s only funny until someone loses an eye.” You begin repeating the inane phrases your mother did - - the ones you swore you’d never say -- until you realize you’ve somehow managed to become your mother.

With motherhood comes the amazing physical ability to love, nurture and parent, and you discover that your body is a harbor, a food source, a shelter… but a Wonderland? Not so much. You are all touched out. You have held and coddled and consoled and nursed and hugged and physically cajoled and by the time your man comes home at night searching for a little nookie, offering your body to one more human feels akin to organ donation.

With a job, four kids and two dogs, there are nights now at age fifty that I’d rather lower myself into an aquarium of hungry piranhas than offer myself up to this man I love. Getting eaten alive by fish is at least passive. It requires very little exertion on my part. And this from a woman who loves her husband. Okay, maybe that last part was a little harsh, but getting down on all fours and purring like a kitten is about the last thing on my list after a long day of taking care of everyone and everything else.

In the beginning you might believe that love has the power to help you change someone; make them better, deeper, more sensitive, more compatible. You believe there is a perfect yin to your yang. And love does have power to change some things, at least to a degree. But you can’t really change them deep down. Not fundamentally anyway. That part has already been molded, the foundation laid years before you came on the scene. You might train them to hang up their clothes and make their beds, to grill and take out the garbage. But the really important stuff, like your philosophy on raising kids, you’r your religion, or your desire to backpack in third world countries, those things can be harder to compromise on. So you’d better look closely and hopefully you’ll get lucky too. After all, there’s a big does of luck in this “forever after” stuff.

Time, life, routine and details become the sand paper, the Emory board that can wear love down in a marriage, leaving a couple shaking their heads and wondering how it slipped away. And so every once in a while you need to pick your marriage up by the seams and shake it, examine it, talk about it, worry about it. You need to face it down.

As hard as it may be to find the time, it’s important to set it aside, draw a circle on your calendar, put in the hard work to buff up the mutual respect, the sense of humor, the ability to admit when you’re wrong and say “I’m sorry” when you are. You need to systematically interrupt the business of living and go to work to shore up the edges—before it gets to the point where it’s irreparably injured, before it has no heart beat and can’t ever pang again.

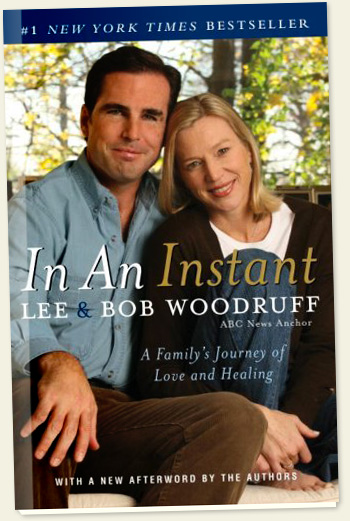

My husband was critically injured by a roadside bomb in 2006 while covering the Iraq war for ABC News. That was a wake up call -- literally at 7:00 am -- that no family should ever receive.

Bob had just been named co-anchor of “World News Tonight” and he was reporting from Iraq for the eighth time. Our life leading up to that phone call was in a good place. We were happy and content, and although we knew that his job would require increasing amounts of travel, we also knew we would find a balance.

Even before the injury, I would have described us as a family who already “got it.” We understood life was precious and short. Maybe we didn’t live embracing that credo every single day, but who really does outside of an ashram? We tried. We’d been through miscarriages, losing a child during pregnancy, a hysterectomy, the heartbreak of a child with a hearing disability, the tragic death of a close family friend. Together we had fingered the tenuous threads that hold us all here on earth. And these things had strengthened us as a couple in their aftermath.

A crisis often has a way of reprioritizing everything. In an instant, my world was rocked with the sudden news of Bob’s injury. And as I stared at him in his coma and listened to all the pronouncements of what the doctors thought he would and wouldn’t be able to do, I wanted more than anything else in the world for him to wake up, to talk to me, to make love one more time.

Over the next year I would become a devoted caregiver. Our relationship had gone from equal footing to one that wobbled unevenly. All at once I was mother, nurse and therapist. I was grieving the loss of someone who was still alive, someone who had an uncertain future. With a head injury, no one can tell you how it will turn out, how much they will recover. What would this new man be like? What if, in the process of caring for him, I began to lose love? What if he remained broken and all of the things I respected—his intelligence, his ability to care for me—what if all of that was in jeopardy?

I never thought for a minute about leaving. Not once. Maybe that’s hard to believe, but I loved this man and I assumed that if he never returned to his former self, I would learn to love him in a different way if he never returned to his former self. I created a back-up plan just to ease my anxious mind during those regular 3:00 am wake-ups. I would go back to work full-time, sell the house, celebrate the things that were still there, the parts of my life that brought happiness. I would find ways, if I needed to, to fill the gaps in my soul with close girlfriends, stimulating conversation and the escape of my writing life.

I had taken my wedding vows seriously and we’d enjoyed some amazing years together, full of extremes – both adventure and routine. We’d produced four terrific children. I would make our new situation work and honor him if he never really recovered. I would give him his dignity if he was unable to work again, no matter how tough that road might be.

In the hospital, staring at his swollen head and his face mangled from the shrapnel, I decided that if he were going to be a vegetable, at least he would be my vegetable. I would take this day-by-day. There wasn’t a doubt in my mind that he would do the same for me.

Luckily, my man returned. He came back in an amazing way with a lot of determination, time and the love of family and friends. He has defied every expectation and his recovery is nothing short of a miracle. That’s a pretty strong word but I have to say it applies here. I’m not going to minimize or gloss over this part. It was hard work. And there were plenty of moments of despair and doubt and terror and grief. There was regret and sadness and depression on my part and feeling emptier on days when I had to buck everyone else up- emptier than the emptiest vessel. And there are moments still where I can feel the damage that was done to all of us by that insurgent’s bomb. Every trauma leaves its scars.

But in the aftermath of Bob’s injury, once he was back at work and well on his way to becoming himself again, I crashed. What had been so “up” for all of those months, had to come down at some point. For months, I battled with the enormity of what had happened to us, the devastation and the post-traumatic stress giving way to disbelief and soul-sucking sorrow. And when I took that dive, Bob was there for me, just as I’d been for him. That’s the amazing thing about a strong marriage. The give and take. You can’t script that, and you can’t perscribe it, all you can do is feel your way along with no road map. You use your gut and your toes, your instinct and your generosity. You may fumble sometimes, but if you’ve laid the groundwork and built the foundation, the center holds.

I don’t recommend tragedy to bring people closer. It doesn’t always work. I’ve known couples that divorced under the strain of illness or children with disease or disability. Hardship doesn’t always bring out the best in people and I can’t pretend to have a formula for how it worked for us. Not every day felt good or hopeful.

But as I write this in the bright sunlight of a July morning, four and a half years after his injury, my husband has already walked the dogs and gotten breakfast. There is bacon on the stove and the trash is already out by the curb. Our kids will be stirring soon and they will gradually tumble down the stairs in various states of awakening. At some point in the day, we will both look around us and be awash in the unarticulated goodness that makes up our lives. It’s a feeling I have when I look at each member of my family and realize we have survived. And our love has grown and aged in different ways. It is richer now, more mellow, like a good stinky cheese. We’ve mostly moved past that horrible time. The big thing that happened to us no longer defines us.

And so we all move forward. We are closing in on a quarter century of marriage now.

I can’t tell you that we’re religious about “date nights,” about having long, intricate conversations and regular sex. Many times we don’t exactly know what the other person is doing or has planned. I’m not always up on what news stories my husband is working on or where is he traveling on a given week, and he doesn’t always know what articles I may be writing. Our lives are full and busy and I am grateful for that—even though the flip side of busy can be stress, fatigue and an occasional lost sense of connection.

Marriage is far more work than they ever tell you. Or maybe we just can’t fathom it at the time. I think about that naïve couple we were—standing in front of the altar flanked by friends and family, believing that the whole world streamed out before us, that it was ours to fashion and make in a way of our choosing. And, to a degree, it was.

One of the hard things about surviving decades of marriage and life itself is to make peace with the fact that at a certain age, though you still feel mentally young, many of the roads have already been taken. The key choices have been made (unless you’re a serial divorcee). There are no big surprises left - - except possibly the ones you don’t want to contemplate; the ones that involve loss. Don’t get me wrong, there are still lots of wonderful moments to anticipate. But exciting, yet-to-be-revealed things like my choice of career, the man I’ll marry, the children I’ll raise – these blanks have all been filled in. My parents are aging and failing. There is poignancy in watching the seesaw tip as my sisters and I begin to parent them in the circle of life.

I often revisit a conversation I had with a family friend, the mother of two boys we grew up with during our summers in the Adirondack Mountains. At 72 she was dying of ovarian cancer. She was honest and open about this fact when I went to visit her for what would be the last time. In that candid way you can afford to be with someone facing their own mortality, I asked her what advice she would give me about marriage; standing as I was, hopefully, in the middle of a long run.

“If I could do it over, “ she said, “I’d leave more dishes in the sink. I’d worry less about the to do lists and leaving my kitchen perfect for the next day. I would have spent more time just sitting on my husband’s lap.”

What a heartbreakingly simple thing to do. Just sit there for a spell, entwined in one another. There is something so basic and pleasurable about just being present. You don’t need words. I try to remind myself of this advice as I rush through my day, fume over Bob’s dirty pile of clothes on the floor or slap together a microwaved family dinner. You’d think that after all I almost lost in my marriage, after everything we’ve been through as a family, that I’d spend every day reaching for gratitude. But we have short memories, we humans. Real life intrudes and I have to remind myself of my friend’s rear view mirror wisdom whenever I feel my foot pressing down on the accelerator.

There are hopefully many chapters yet unwritten in my marriage. But if you’re just looking for the high wire act, the rollercoaster thrill, if you’re a junkie for the eternal sizzle, the fresh piece of flesh and the multiple orgasms, then my words are probably going to fall a little flat. Me? I’m simply happy that my husband and I can reconnect to those parts of ourselves that matter most, the things that brought us both together in the first place. I’m content most nights to aim for sitting on his lap.

Even if I don’t get there as often as I should, I’m happy to focus on that next pang.